Silver for the Poor: The Story of an Illicit Badge

A throughline in almost all of my work is the idea that objects—especially old ones—serve as tangible links between past and present, giving us a visceral connection to lives lived long before our own. Why does that matter?

Maybe it’s enough to say that it’s just plain fun. We love a good historical rabbit hole. We love piecing together the bones of a story and fleshing them out in our imaginations. But objects can also clarify the arc of history—sometimes in ways that make progress feel like a triumph, sometimes like an illusion, and sometimes like a hamster wheel.

I’ll let you decide which one this object represents.

Before I tell you what it is, take a look. Any guesses?

Now, the spoilers: It’s a badge, meant to be sewn onto a sleeve—a token of membership. Given that it’s made of silver, you might assume it signified an elite society, some exclusive club. In fact, it’s the opposite. This badge was made for a poorhouse.

How did one of society’s most destitute come to wear something made of a luxury material?

To answer that, we need to rewind to the reign of Henry VIII. England’s religious establishment was in upheaval as Henry severed ties with the Catholic Church, seizing its wealth and consolidating power over the clergy. The casualties of this rupture ranged from modest monks to high-ranking advisors, many of whom lost their heads.

Against this backdrop, an ambitious clergyman named Robert Holgate (b. 1481) was rising through the ranks, first as Bishop of Llandaff in 1537, then as Archbishop of York in 1545. The perks were substantial. The dissolution of the monasteries meant a windfall of confiscated church property, and Holgate—unencumbered by Catholic vows of celibacy—married a woman 40 years his junior and secured a tidy personal fortune.

Clergyman Robert Holgate, c. 1520

Image from, © Credit.

His fortunes, however, were tethered to the ever-shifting tides of religious politics. When the staunchly Catholic Queen Mary took the throne in 1553, she wasted no time imprisoning him in the Tower of London. In a panic, Holgate renounced both his marriage and his Protestantism—enough to earn his release, but not his former status. He died in obscurity two years later.

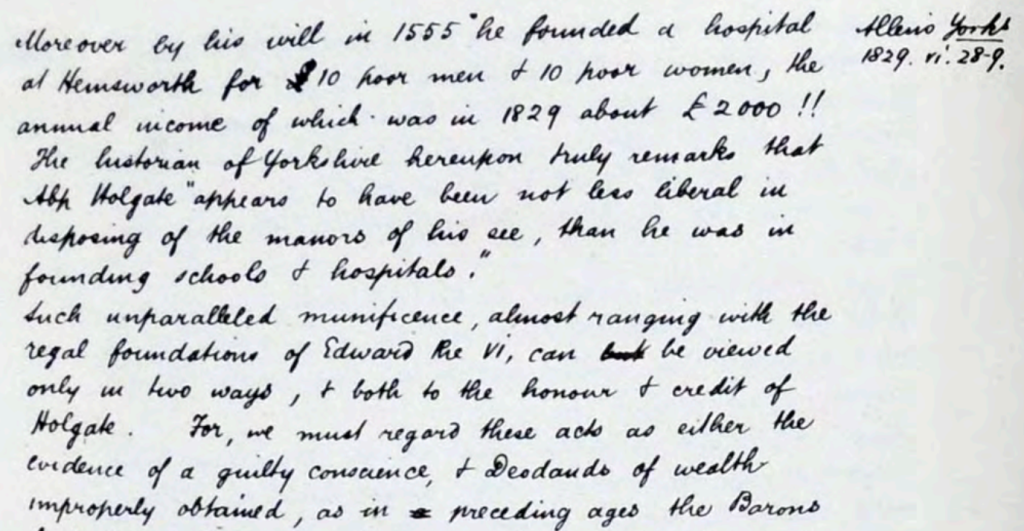

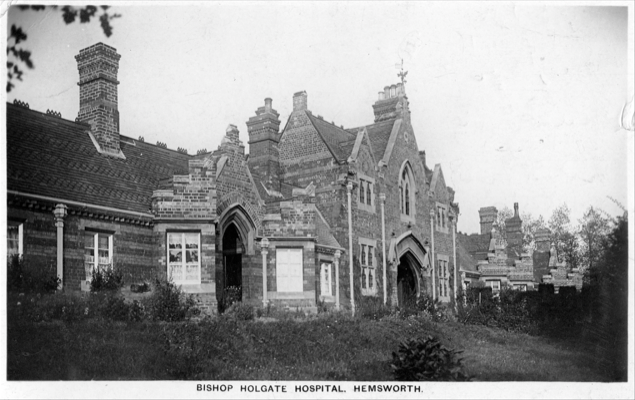

And yet, Holgate’s name endured—not because of his political maneuvering but because of a carefully planned act of charity. In his will, he left funds to establish almshouses for the elderly poor in his hometown of Hemsworth.

The original endowment provided for ten men and ten women, but with conditions. Residents had to abide by a strict moral code: no swearing, no brawling, no visits to the alehouse. There was a curfew. A dress code. And crucially, only the “deserving” poor—read: Protestant, well-behaved, and fallen on hard times through no fault of their own—were eligible.

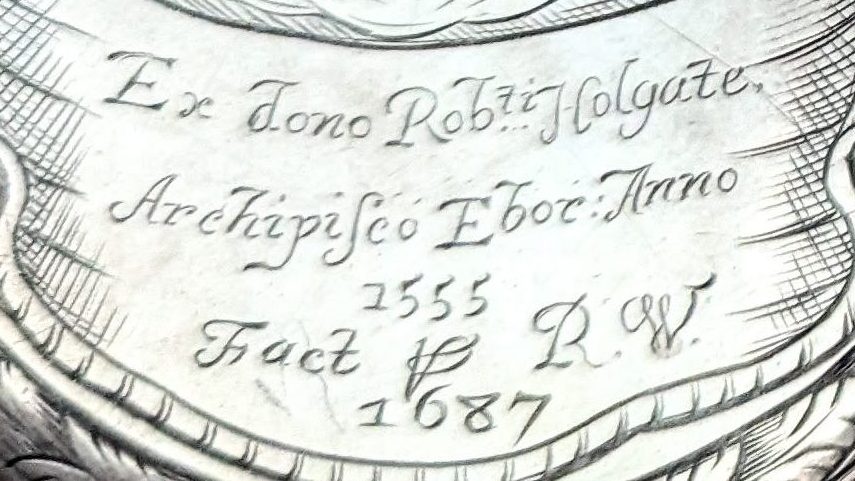

Which brings us back to the badge.The inscription translates to: “Gift of Robert Holgate, Archbishop of York / 1555 / Made for R.W. 1687.” On the reverse, a silversmith’s mark: WN with a dagger, stamped four times.

Holgate’s pensioners received these silver badges to affix to their uniforms, identifying them as members of the almshouse community. Rather than a mark of shame, it seems the badge was a point of pride—an emblem of security in an era when social safety nets were scarce. This particular badge is from a group ordered in 1687.

There is, however, a delicious irony. For all its pious projection, this badge was made illegally. In England, every piece of silver was required to bear hallmarks, proving it had passed through the official assay and tax process. But because this was a private commission, never intended for sale, the silversmith sidestepped regulation—and taxation—by stamping his own mark four times to give the at-a-glance impression that the piece had been properly hallmarked.

So why does this object matter now?Beyond being a beautifully crafted artifact with a rich story nearly 350 years old, it offers a glimpse into the unchanging tensions of social welfare: Who deserves aid? Should charity be private or public? How much control should givers have over recipients’ behavior? The debates that shaped Holgate’s almshouse wouldn’t be out of place today.

To hold this badge in your hand is to connect yourself to the arc of history—and to reflect on which way, if any, it’s bending.