I Wish Everybody Was a Snodgrass

So I hope that for your sake dear reader that you are a Swozzler,

But I hope for everybody’s that you’re not.

And I also wish that everybody else was a nice amiable Snodgrass too,

Because then Life would be just one sweet, harmonious mazurka or gavotte.

—”Are you a Snodgrass, Too?”, Ogden Nash

This pair of porcelain chestnut baskets is more than just a relic of fine craftsmanship—they are artifacts of one of the most brazen charlatans of the British Empire. Or, to put it another way, a model success story of colonial corruption.

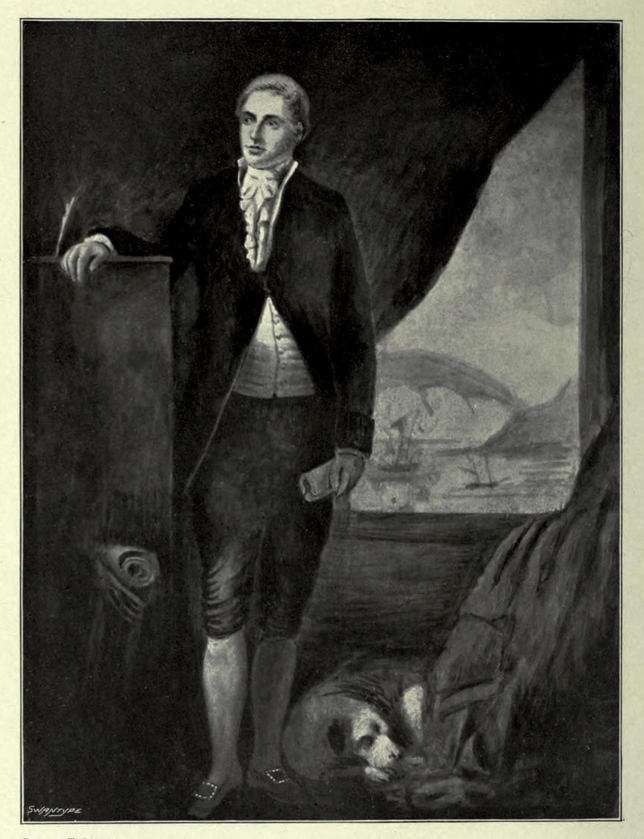

Made in the legendary kilns of China around 1800, these baskets—pierced, glazed, gilt, and impossibly delicate—bear the coat of arms of a certain Mr. Thomas Snodgrass. If the name sounds absurd, rest assured, the man lived up to it.

Snodgrass began his career with the East India Company as a teenager in Chennai. He rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a high level administrator called a Collector (which means exactly what it sounds like). Despite a relatively modest salary, he managed to build an opulent lakeside palace (now a luxury hotel). Where did the money come from? The answer (corruption) was not exactly well hidden.

By 1797, the Company had lost patience. Their evaluation of Snodgrass was blistering: “notorious by the wholesale corruption which he allowed to prevail in every department of Government”; he was accused of “defalcations of the revenue, coupled with fraud and wholesale oppression.” If that weren’t enough, he also evidently encouraged “intrigue, dissipation and extravagance” via “the captivating allurements of a despotic dancing-woman.”

When confronted about expected revenue the Company was missing, Snodgrass blamed the monsoons, civil unrest—really, anyone but himself. The Company’s response was withering: “A more extraordinary statement in extenuation of a gross defalcation of revenue has, we believe, never before been submitted by a Collector.” Under his watch, what had once been a thriving province was reduced to “nearly the last ebb of a depopulated and frightful waste.”

His official rap sheet included:

- “Mismanagement of the revenue administration of Ganjam District”

- “Apology demanded from, for disrespect towards the Government”

- “Enquiry respecting charges of corruption and abuses permitted by, during Collectorship at Ganjam”

Rather than go quietly, Snodgrass did what any self-respecting villain would: he threatened to murder his replacement. Then, in a final act of bureaucratic arson, he loaded his financial records onto a dinghy, rowed to the middle of the lake, and sank them.

After 27 years in India, he was forced back to England, disgraced but fabulously wealthy. The Company, in a rare show of backbone, stripped him of his pension. But Snodgrass, ever the showman, had one more act to play.

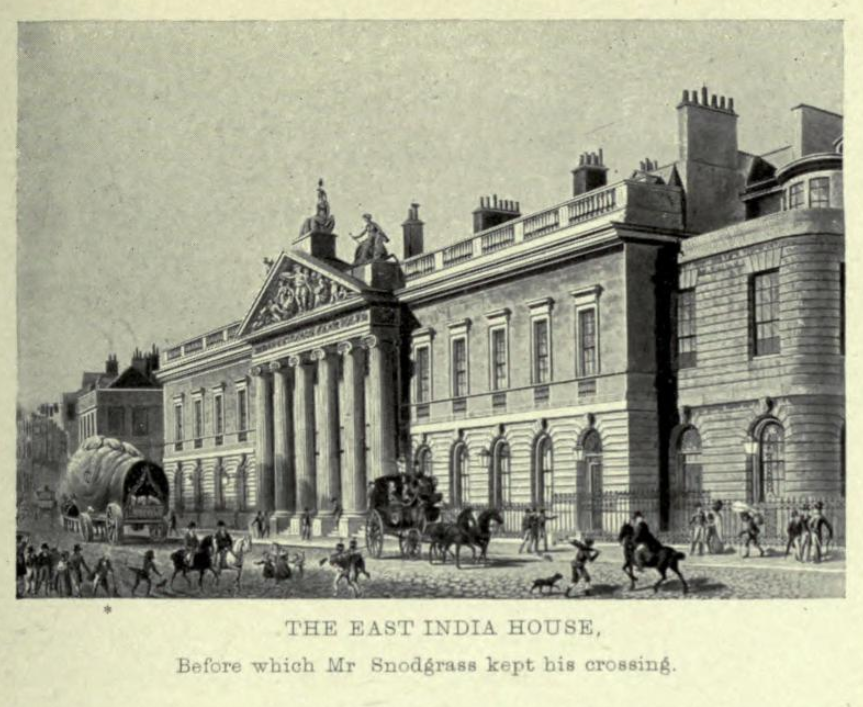

Dressed in rags, he took a job as a street sweeper—conveniently positioned in front of East India House, where he made sure every passerby heard his tragic tale: a loyal servant cast into destitution after decades of service. The Directors, mortified by the public spectacle, caved. Pension restored.

And the very next day?

Mr. Snodgrass, attired in frock coat and tall hat, drove up in a carriage and pair, or rather with four horses…to thank the Court in person for his pension, and, at the conclusion of his address, he is said to have added:—’You have now made up my income to £5,000 a year.’ The feelings of his honourable hearers when he made this frank admission may be better imagined than described.

What became of this unreformed rogue? He settled into London’s elite, securing a house in Mayfair, founding the Oriental Club (shoulder to shoulder with the Duke of Wellington, no less), and generally inserting himself into respectable society.

Having been issued a coat of arms in 1799, Snodgrass saw fit to purchase an extensive Chinese export porcelain service adorned with those arms—including this pair of baskets.

If there’s a moral here, I’d rather not dwell on it. But if they ever make a film about Snodgrass, I’ll be first in line.